The change in our habits, routines and priorities was reflected on our everyday objects.

To capture this extraordinary moment in time, people from all over the world shared their 15 new essentials.

This project captures the moment when everything changed – how we worked, learnt, cared, socialised, entertained, shopped, connected, unwound, even the way we loved. By revealing the objects that matter most to us in lockdowns, this photo archive reveals how our needs and priorities changed as Covid-19 struck.

My journey documenting the objects we interact with on a daily basis started in 2014 with my project-turned-book ‘Every Thing We Touch: A 24 Hour Inventory of our Lives’ (Viking, 2015). The project - an experiment that straddled art, design, research and anthropology - tells the stories of people from around the world through individual photos of everything they touched in one day, presenting all their everyday items in chronological order, from dawn to dusk.

I realised that this project, which covered people from all ages and backgrounds across all continents, had archaeological value. It was a time capsule of how we lived our daily lives. What would future generations learn about us when they saw these photographs?

Archaeologically found artefacts have taught us everything we know about past civilisations. They revealed how their societies lived, worked, played, cooked and expressed themselves. I named my journey Future Archeology : this title challenges us to imagine what future generations will discover about our habits, needs and desires when they study and decode our essential everyday objects.

When the Covid-19 arrived, I couldn’t help but notice a shift in the objects we were using every day. Lockdown meant reorganising our lives, which changed the functional and emotional items we needed every day. As someone who believes in the power of everyday objects to tell our stories, I gathered my own newly assessed 15 essentials and captured them in a single photograph, mimicking the style of Every Thing We Touch. How would other people’s essentials have changed? Sensing the profound scale and global reach of the pandemic upheaval, I was eager to find out.

Working within the confines of quarantine, I posted my 15 essentials on Instagram under the hashtag #EveryThingWeTouchCovidEssentialsX15 and invited friends and strangers alike to join in: “What are the fifteen things that are helping you get through this?”

Maybe they’re new things that have come into your life. Forgotten items that have suddenly become relevant. Familiar things that have taken a new meaning. What are the things helping you survive, love, resist, care, connect, fight, hope, enjoy, forget, escape or just be? And what do they say about our individual selves and our global community?’

Grateful to encounter tags from across the world, I started tracking each person to collate their images and build this time capsule. It felt like I was taking a large photograph of a paradigm shift. But this time without leaving my house – and with no camera in hand.

My journey documenting the objects we interact with on a daily basis started in 2014 with my project-turned-book ‘Every Thing We Touch: A 24 Hour Inventory of our Lives’ (Viking, 2015). The project - an experiment that straddled art, design, research and anthropology - tells the stories of people from around the world through individual photos of everything they touched in one day, presenting all their everyday items in chronological order, from dawn to dusk.

I realised that this project, which covered people from all ages and backgrounds across all continents, had archaeological value. It was a time capsule of how we lived our daily lives. What would future generations learn about us when they saw these photographs?

Archaeologically found artefacts have taught us everything we know about past civilisations. They revealed how their societies lived, worked, played, cooked and expressed themselves. I named my journey Future Archeology : this title challenges us to imagine what future generations will discover about our habits, needs and desires when they study and decode our essential everyday objects.

When the Covid-19 arrived, I couldn’t help but notice a shift in the objects we were using every day. Lockdown meant reorganising our lives, which changed the functional and emotional items we needed every day. As someone who believes in the power of everyday objects to tell our stories, I gathered my own newly assessed 15 essentials and captured them in a single photograph, mimicking the style of Every Thing We Touch. How would other people’s essentials have changed? Sensing the profound scale and global reach of the pandemic upheaval, I was eager to find out.

Working within the confines of quarantine, I posted my 15 essentials on Instagram under the hashtag #EveryThingWeTouchCovidEssentialsX15 and invited friends and strangers alike to join in: “What are the fifteen things that are helping you get through this?”

Maybe they’re new things that have come into your life. Forgotten items that have suddenly become relevant. Familiar things that have taken a new meaning. What are the things helping you survive, love, resist, care, connect, fight, hope, enjoy, forget, escape or just be? And what do they say about our individual selves and our global community?’

Grateful to encounter tags from across the world, I started tracking each person to collate their images and build this time capsule. It felt like I was taking a large photograph of a paradigm shift. But this time without leaving my house – and with no camera in hand.

Matt Shunshin, London - United Kingdom.

Cardiologist, NHS Covid-19 wards.

The Oliveros - Mata family. “We share more spaces, moments and objects than before and this sofa has become our hotspot”.

Naitiemu Nyanjom, Nairobi - Kenya.

“Pinky squirrel - cos why not?”

Laura Maggi, Milan - Italy.

Laura Maggi, Milan - Italy. “A birthday candle for all of those Aries and Taurus Zoom parties”

Chris Butler, Portland - USA.

“A bell for the 7 PM essential workers shout out on the streets of Portland”

Kevin Katsura, Buenos Aires - Argentina.

“Jump leads, to jump start my car every time I drive”.

Liliana Cadena, Barichara - Colombia. “Hormigas Culonas (big-bottomed edible ants), reappreciating nutritious home-grown local food by the people in our communities.”

Martín Género, Santa Fé - Argentina.

“Home made barbel and weights I made with my brothers when the gym closed down”

Rina Goto, Tokyo - Japan.

“Things will work out”.

Agustina Hassenbruk, Misiones - Argentina. “Repellent, an everyday essential to fight Dengue” and “Mate, I can no longer share it with my dad”

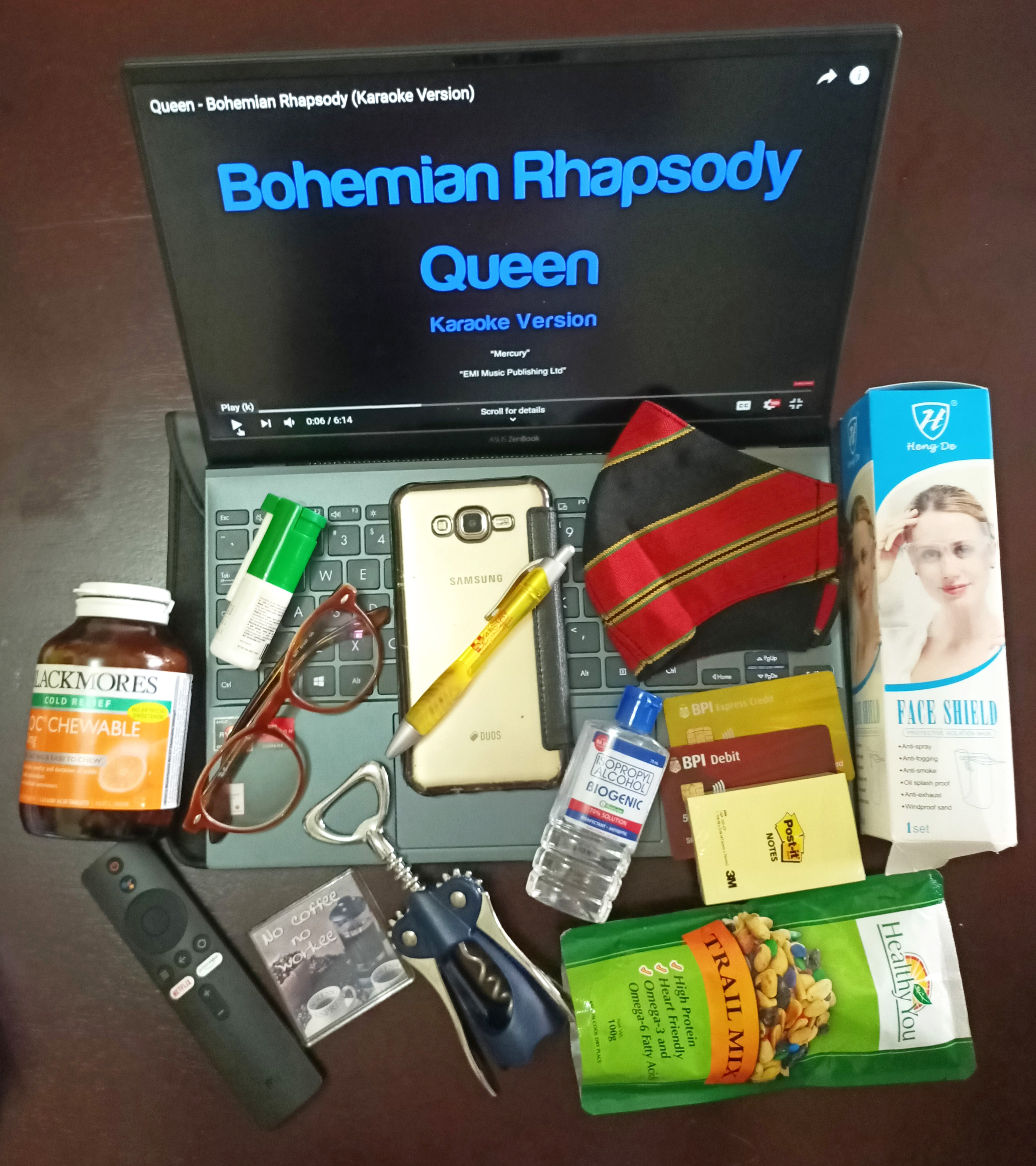

Sharon, Manila - Philippines.

“Bohemian Rhapsody by Queen, playing Karaoke by Zoom”

María Belén Morales, Quito - Ecuador.

“Shamanic drum, Agua de Florida, Abuelo Fuego”

This archive

This website collates over 1,000 stories from 50 countries : from Kenya to Japan (albeit weighted towards the UK, which is where I live, and Argentina where I’m from); and from kids and teens to the elderly.Classified first by country then by city of location, each photo is accompanied by a title and an unedited personal narrative that supports the objects. To view the text in your preferred language, use Chrome and download the Translate Extension, then click on the icon (top right corner of your browser) to change the language of the web. You can explore the web with no location filters at random or searching by family groups.

All photos were taken by their authors and their location is HOME, or what was ‘home’ during quarantine. Many left home to reunite with loved ones, offer support, quit the city or downsize. Others were stranded in the attempt to make it home. The majority stayed at home: the minority were essential workers on the front line.

The result is raw. It exposes how we found ourselves at the moment we had to stop. Rather than enhancing our home for the shot, dressing up to pose or finding the best filter for the selfie, these images found us underdressed, without make-up, with hair in a mess and trying to adjust.

Learnings

This project is not just for future generations. It encourages us all to look at ourselves in a different light and invites us to pause, think and reflect. What do our objects say about us and how do they express our needs, hopes and fears?The beauty of the archive is that everyone will see something different in it. My words below will guide you through the following:

How do I look at it? And what do I see?

While the project allows us to dive into cultural and regional differences, it also exposes our essential similarities. Most importantly, it affirms that humanity transcends borders and cultures. And Covid-19 affected us all.

This is not to say we all experienced it similarly. As the Mental Health Foundation said, “We are all in the same storm, but we are not all in the same boat”. People’s experience depended on their social and economic context. Looking beyond borders enriches your perspective by revealing diverse experiences and points of view.

I invite you to explore this site with the eye and the mind of an ethnographer. To learn by seeing things from the perspective of others.

In my professional practice, I always highlight the difference between making sense of others and making sense of how others make sense. The former is conditioned by your judgement, because you see things from where you stand. The latter allows you to understand someone’s mindset, because you strive to see the world from their eyes. This unlocks different belief systems and how they affect needs, priorities, behaviour, values and choice (when choice exists).

When you know how others make sense, you don’t see opposites, you see diversity. You don’t see a winning or losing path, you see multiple future scenarios that take into account many people’s different needs.

Just as with any photograph of ourselves, our 15 essentials will never be the same. In my work, I find that the questions I get asked about the future (what’s the future of fashion? banking? wellbeing? work? Luxury?) hide a truth: we don’t understand the present. This is because there isn’t just one present. It’s not linear, we can’t see where the horizon is and the viewer can’t find their own eye level. This discomfort manifests itself in our desire to be told where and what the future is so we can get ready for it.

What I teach my students is:

1) Understand the present. See what is happening, but see it from different points of view.

2) Go back to the past. Look for patterns, identify change.

3) Think about the future. Use imagination and wisdom when you do.

We should all understand by now that the effect of Covid-19 isn’t a stand-by pause putting our lives on hold between the past and the future. It’s our present. The paradigm changed and we need to create our future from here. The way we do everything is not the way we used to do everything. We need new international and public policies to create a better people-planet ecosystem for us all.

With that in mind, what are these photographs telling us about our present? What do we see here that is different from the way we did things before?

Let's look for patterns and highlight the change. Let’s see what we like and dislike about our new behaviours so we can think about our future with imagination and wisdom and develop strategies with a long-term positive impact.

What are our essentials when there is no beholder?

Most revealing is that brands - per se - were not part of this conversation. In fact, independent local producers and makers were mentioned or tagged instead. Accustomed to capturing the fabric of daily life as a global ethnographer for over 20 years, it was refreshing for me to see that assets such as product functionality, comfort and feel, and emotional attributes such as ‘this grounds me’ are used to present or define our belongings. Brands were incidental to the object, for example an Adidas logo features in a photo because ‘my sliders are essential’. (In case you’re wondering, the brands that appeared the most are Apple, Nike and Adidas).

Choices were introvert rather than extrovert, seen across different product categories. Fashion prioritised comfort over looks, elevating the fit and material of the garment above all else. There are no handbags, accessories high heels in the photos, yet there are hoodies, tracksuits, trainers, slippers and blankets. It is the same with beauty; personal pampering such as lotions, exfoliators, serums and salts took precedence over lipsticks, foundations and eyeshadows. The focus was on us.

Capitalist consumption means often, purchases and choices are made with the eye of the beholder in mind. We care about their impact on the observers: colleagues, friends, guests, people at the party. Lockdown removed these filters. The absence of beholders flipped the priorities purely to the self. Every choice is oriented towards personal comfort, safety and mental and physical wellbeing: of you and the people you live with. Material luxury existed too, however not expressed with logos but instead cherishing sensory pleasures such as “the long-lasting scent of that candle”, “the cashmere on that blanket”, “the taste of that exclusive gin”.

How do we present ourselves from the intimacy of our homes?

The participants told things as they are - their home, their rules - and were honest about how they felt. The photos speak about our state of being, and honour our vulnerability and honesty. We encounter photo titles such as: “things we need to keep sane”, “to remind myself who I am”, “to feel alive”, “to take care of myself”, “to not feel alone”, “to get to know myself”.

Furthermore, the objects that tell these stories have no stigmas attached: sleeping pills, antidepressants, cannabis, books about mental health, sex toys and alcohol. These are the things that one might expect people to hide. They speak of frankness. Is there curation involved? Sure, every picture is composed by its author, and every author has a story. Yet the stories are authentic as they expose the way the global pandemic made us feel.

The absolute and relative value of objects The deliberate act of placing an object on a canvas is the realisation of its importance beyond its absolute value. It imbues the object with meaning and reveals its relative value.

If we see an object as just, say, a speaker, that’s its absolute value. It is what it is.

Adding the statement “it makes me dance and forget” gives it meaning and imbues it with relative value.

For example, a birthday candle spotted in an Italian photo in isolation is only of absolute value. However, the statement “for all of those Aries and Taurus Zoom parties” gives meaning to the object. Now, that candle resonates with anyone who has celebrated a 2020 birthday on Zoom. Objects unlock stories and memories

A bell placed in a photo from America became a proxy to “show appreciation to essential workers at 7PM on the streets of Portland”. In the United Kingdom, people clapped.

A headband seen in an English photo became something “to cover my grey hairs on a Zoom call” as UK hair salons were closed during Covid-19.

A set of jump leads in an Argentine photo became the essential catalyst to car keys: “the battery of my car keeps going flat, I have to jump start it every time I drive.” Argentineans were not allowed to leave their homes without a government permit.

And this is what archaeologist and historians work hardest at. Not to classify artefacts, but to decode the usage, meaning and behaviour behind them. What were people actually doing with this thing?

If we consider both absolute and relative aspects with an emphasis on what is different from the world before Covid-19, we can classify our essentials into:

Inevitable objects: Laptops, mobile phones and tablets are in most photos, regardless of location. Devices and applications enabled work, education, entertainment, health, information, communication, celebration, shopping and banking more than ever. We seemingly reconciled our relationships with screens while all aspects of life witnessed digital acceleration. Alongside the screens, we usually find a mise-en-place of objects to help out with the privacy and good ergonomics people need when all their life activities have converged within these devices: headphones; reading glasses intentionally placed by new users coping with screen overdose; and sometimes, eyedrops and devices to fight repetitive strain injury (RSI).

Empowering objects: DIY, decorating and gardening tools - supported by YouTube tutorials made by people who are kinder and more generous than manufacturers - gave us new skills. These represent the satisfaction of new accomplishments by doing things ourselves. Driven by the absence of third-party services and the need to solve problems at home, everyone learnt something new. Things were fixed (we see Superglue) and taken better care of. In-sourcing became a thing and we skilled up. Hair clippers say “I cut my own hair for the first time”.

Detour items: Think of ‘detour’ as the antonym of ’shortcut’. The first months of lockdown brought scarcity to our lives. For some it meant shortage of food, for others, simple shortage of variety and choice. Accustomed to having things ready-made, we were compelled to take the long way round to get them. So, we made our own bread, grew our own food, cooked our own food and consciously picked the ingredients. The objects bear witness to this: rediscovered cooking utensils, vegetable seeds in urban contexts, the emphasis on local produce and the inclusion of natural immunity boosters in daily diets. We reconnected with forgotten knowledge and processes and took the opportunity to bring food and health closer together.

Saviour items: Literature, film, music and podcasts saved us. The majority of photos reference one of these and their importance. Culture informed, entertained and inspired us. Luckily for books, since people still prefer the physical format, their titles can be traced and a list of what people read in quarantine will soon be here. It’s less likely for music, where we can only tell what people are listening to if they chose vinyl. Media is something that we stopped ‘touching’ a while ago; there were no CDs nor DVDs to tell their stories. People typically refer to ‘Netflix’ or ‘Spotify’ as to what they are watching or listening as well as what they consume within social media. Gaming was a saviour for kids and adults too. PlayStation, Xbox and Nintendo Switch were an escape, a pastime and way of connecting with others. Home-schooled children created stronger links with their peers taking to each other while playing Fortnite than over Google Classroom, as it offered the freedom of the missing playground.

Objects that lived the dream: Sewing and baking machines, old musical instruments, easels, watercolours or film cameras came down from the attic to fulfil their original intent. We tend to buy or hold on to items that are not about who we really are in the present, but an idealised version of ourselves that will come into being when we have time. At least, we could be this idealised self. And for those true artists and musicians, quarantine gifted them with more creative time.

Scenographic objects: Candles, lights, incense, and speakers were vital to transforming our confined spaces and creating ambience and flexibility, transforming the daytime working sofa into a relaxing zone for the evening. Sensorially, these objects altered the perception of the seamless daily grind and were often accompanied by newly developed shrine-like routines. We connected to our spaces in a different way, spending the entire day inside, observing how sunlight projected differently by the hour over our homes, and seeing plants, seeds and flowers grow.

Recreational objects: Before Covid-19, adults did not play games so much as part of everyday life. Board games and cards became household essentials to spend time together while jigsaws, crafts and colouring books offered ways to escape and kill boredom. There were no pubs, no clubs, no restaurants, no festivals, no dinner parties. Games brought us closer together and were adapted to play across screens, bridging the gap between distant families and friends.

Resetting objects: Running shoes, footballs, bikes, skates, sunglasses and dog leashes were magical; they were the connector to fresh air and a fresh mind. Using them meant resetting and often the best part of the day.

Grounding objects: The focus on wellbeing was paramount, as seen in healthy and natural food ingredients and vitamin boosters, but most notably gym equipment as something new imported to the home. Most homes acquired some form of gear, bought, borrowed or built. Yoga mats became magic carpets for escape in and resistance bands stood in for heavy weights. Taking control of our fitness and wellbeing gave everyone the sense that things were going to be under control. Whether they are used or not, objects have the power of projecting the desired emotions just by the mere fact of their existence in our lives.

Sentient items: Sentience is the capacity to feel, perceive or experience subjectively. The time to stay still and put busy lifestyles on hold invited notepads and journals for jotting down thoughts and feelings, representing a wider reflection time. People looked inwards and important lifestyle decisions were questioned during the pandemic. Is my life sustainable? Am I where I want and need to be? The large presence of religious and spiritual items reflects the need for guidance to navigate this time. And objects with graphic messages such us “things will work out” reflect the desire to share these feeling with others.

Emblematic objects: While face coverings were ubiquitous in public spaces in many Asian countries before the pandemic, this is the product Covid-19 introduced to us all worldwide, followed closely by face shields, hand sanitiser, ethanol disinfectant, sterilising gloves and a plethora of household cleaning products. Beyond their hygienic functionality, these items equally represent Hope and Fear. We also see “going out kits” armed with protection and large shopping bags for one-off essential outings as well as “landing stations” with buckets and disinfectants to shield our homes from the outside world or simply receive the post.

What were the similarities and how did cultural differences manifest?

Looking at the photos by country, we can spot objects that tell us about new changes in behaviour at a local level and the peculiarities of how Covid affected each society or how the society responded to it.

In Kenya and Nigeria, bibles told us about people attending mass at home via Facebook as meeting at places of worship was not allowed. Communities felt torn apart, unable to congregate to deal with the crisis together.

In the Philippines, a laptop has Bohemian Rhapsody by Queen on its screen. Karaoke, a favourite Filipino pastime, moved in-home on Zoom as bars were closed. Later, the government banned the in-home version too, as it considered the noise to infringe curfew hours.

In South Africa, the ban on alcohol and tobacco was referenced, featuring a Savanna apple cider bottle secured as the ban began.

In Argentina, mosquito repellent tells us how the country was fighting Covid-19 and Dengue at the same time.

In Kenya we see a round item with a string representing a Matatu. A Matatu, the typical Nairobi taxi bus, is the backbone of Kenyan public transport; and the round item with a string is a charm you’ll find as decoration on the inside. The Matatu here is an essential item for a maternity nurse to commute to the local hospital. Matatus, which usually carry ore passengers than they have seats, were early adopters of change during the crisis. They were forced to observe social distancing, offer sanitation and demand digital cashless payments.

In the United Kingdom, eggs were placed in photos to highlight their scarcity and people felt the need to print out the logo of Joe Wicks, who became the nation’s PE teacher as he live-streamed daily classes to keep children active.

In a photo from Ecuador, a shamanic drum is used as a guide teacher and healer alongside Agua de Florida and a candle representing the indigenous deity Abuelo Fuego.

If you are interested in cultural texture and colour, ‘hot drinks’ is a good category to look at, as every society needed their tea, coffee, macha, malt chocolate powder or yerba mate to survive. Argentines are obsessed by mate, which is traditionally shared and sipped through the same metal straw amongst friends and family. However, Covid-19 spoiled this habit. Mate became an individual experience for the first time. The photographs reveal each territory’s hot drinks rituals as well as their specific vessels and brands. Another interesting tour to take is ‘snacks around the world’.

The beauty of the archive is that everyone will see something different in it.

What do you see? info@lockdownessentials.org

Acknowledgements

This is an independent project that would not be possible without the participation of everyone whose photos you see here. Thank you to all the contributors for sharing your photos and reflections to create this time capsule.If you sent your photo but can’t find it, the resolution will have been too small. Please resend higher than 1MB along with your description.

Academic Institutions

In addition to the hundreds of individuals who contributed their story, this project benefited enormously from the participation of several academic institutions around the world across the fields of design, art, communication, media and the social sciences.Encouraged by teachers who found the project of interest, hundreds of students connected with each other to share their newly assessed “15 essentials” in virtual classes. The images plastered the virtual boards of Padlet, Mural and Miro as students presented their lockdown life while reflecting on the impact of the pandemic changing our daily needs and desires.